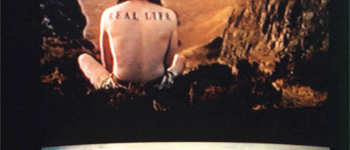

Real Life Rocky Mountain

CCA, Glasgow

8m x 7m x5m

|

For the duration of the show I am present, my back to the audience, Real Life tattoo clearly visible, singing my heart out. Everything in this work is visibly false, fake, ersatz. The mountain is constructed from a wooden armature covered with M.D.F. ribs, chicken-wire and plastic grass. There are fibreglass rocks and trees, with electronic waterfalls coruscating past the many stuffed animals populating the hillside ; fox, capercallie, stoat, rabbit, wildcat, hooded crow, raven, goat and weasel, all indigenous to the locale.

The only thing that is real is me, singing, sitting, on a glass fibre rock on a plateau half way up this construction. The songs I sing are drawn from three periods in the history and tradition of Scottish popular songs ; the late 18th century, early 20th century and late 20th century.

I begins with songs from, amongst others, Lady Nairne and Robert Burns. Many of these songs are politically motivated focusing on the last of the Jacobite Rebellions in 1745, the last time Scotland was close to political autonomy. Then there are others which are simple, beautiful love songs. Many of these are themselves based on melodies and fragments of lyrics gathered from an oral tradition going back to the middle ages. There are songs from the early 20th century from what became known as the Scottish Music Hall tradition. Performers such as Will Fyffe and Harry Lauder travelled far and wide across the globe with their brand of kitsch tartanry and in many ways reified a questionable global perception of the Scots which persists to this day. These performers were very successful, big stars of their day, particularly in London and in America. This cliché, heavily romanticising and mythologising Scotland’s history and influenced by the fictions of Sir Walter Scott, spread rapidly until the perception of Scots as kilt wearing drunkards, who are parsimonious in the extreme, becomes accepted history when it was, in fact, based on nothing more than a comedic myth. Finally I sang songs from the last decade from artists such as Teenage Fanclub and Edwyn Collins which reflect the experience of living today in a small northern European nation.

Real Life Rocky Mountain uses popular music as a lens through which to re-focus the cultural and political development of a small country at the end of the twentieth century. It gently warns of the dangers of the emergence of theme park nations, completely subsumed into the heritage industry where the popular myths of history (which often never quite existed in the first place) are re-created for the global tourist. Is it possible that small nations which have, historically, been emasculated by a more powerful neighbour successfully reinvent themselves in an international political and cultural dialogue? Real Life Rocky Mountain asks where the cultural heritage of any nation actually resides, in politics, history books, geography, memory or fiction? And could this change in perception become part of that dialogue when we consider that countries past, present and future? The Sound of Young Scotland Part 2 Vol. 2. A video shows my real life character singing traditional Scottish songs in the Highlands and Islands, often in the specific geographic locations from which they were inspired. Shot in such a way to render the whole of modern civilisation invisible, no roads, no cars, no buildings, nothing at all except me, Real Life tattoo framed from behind as usual, singing at the top of my lungs into the timeless emptiness of the remote countryside. Standing in the gallery in a busy city centre watching this video, one was free to ponder the distance, physical and psychological, between the context where one is standing and this other location, ambiguous in place and time.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||